Migration is as old as life itself—an instinctive movement in pursuit of survival, livelihood, and growth. Birds follow the seasons, rivers carve new paths, and people move across lands. Yet in the age of borders and bureaucracies, migration is no longer merely a passage—it is a negotiation of identity, belonging, and sometimes, survival.

For the Indian Gorkhas, this journey began not with an exodus but with expansion—voluntary, strategic, and organic. Long before the modern nation-states of Nepal and India took form, the rugged Himalayan corridors that now straddle the borders were home to myriad communities, including those who would later be known as the Gorkhas. This story, of their movement, settlement, and evolution, is one that spans over 300 years—intertwined with wars, treaties, colonial ambitions, and an enduring quest for identity.

The Pre-Colonial Geopolitical Landscape

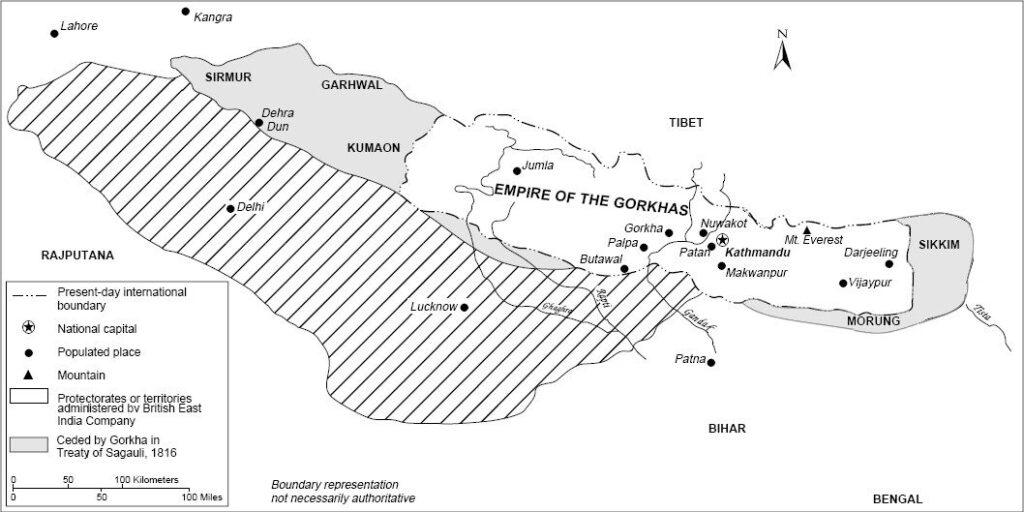

The lands we now associate with the Indian Gorkha community—Darjeeling, Kalimpong, Sikkim, parts of the Northeast—were once part of different kingdoms with fluid territorial arrangements. Darjeeling belonged to Sikkim, which, for nearly three decades in the late 18th and early 19th century, was annexed by Nepal until the Anglo-Nepalese War forced a reversal (Subba, T., 2018). Kalimpong, by contrast, was part of Bhutan until it was merged with Darjeeling by the British in 1864 (Malley, 1907).

The historical landscape was far from static. Conquests and realignments frequently altered jurisdiction over these lands, and with them, the people living there. The idea of a fixed “border” between Nepal and India is a relatively recent creation—one that arose from a war.

The Gorkha War and the Treaty That Redrew the Map

The Anglo-Nepalese War (1 November 1814 – 4 March 1816), also known as the Gorkha War, was a turning point in Himalayan geopolitics. The war was ignited by competing territorial ambitions: the British East India Company sought to protect trade routes and expand its northern frontiers, while the Gorkha-ruled Kingdom of Nepal was undergoing a period of aggressive territorial expansion.

P.C: Unknown author – Public domain – https://www.indianculture.gov.in: https://www.indianculture.gov.in/rarebooks/cassells-illustrated-history-india-vol-i

Despite valiant resistance by Nepalese forces in the unforgiving mountain terrain, the war culminated in defeat for Nepal and the signing of the Treaty of Segowlee (or Sugauli) in 1815 (ratified in 1816). Nepal was forced to cede nearly one-third of its territory, including Sikkim, Kumaon, Garhwal, and parts of the Terai region (Singh, 2010). This treaty effectively established the modern India-Nepal border and divided the Nepali-speaking population across two nations.

P.C: By Unknown author, most likely Keshar Shumsher or S.R. Tickell – scan from a book, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17854778

Colonial Recruitment and Cultural Displacement

In a twist of colonial irony, the British, deeply impressed by the martial prowess of their former adversaries, began recruiting Gorkhas into their army almost immediately after the war. Recruitment began in 1815, even before the treaty was ratified, marking the start of a long military relationship between the British and Gorkhas.

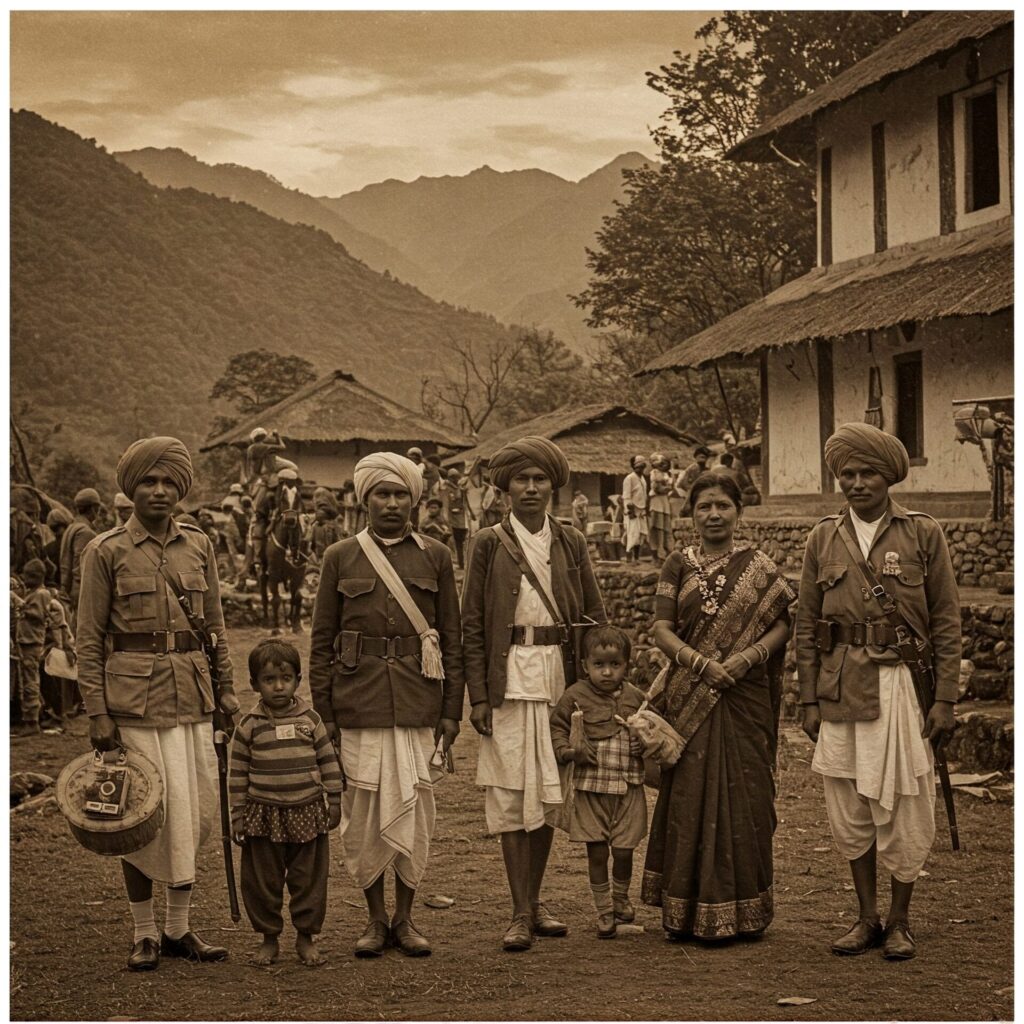

Recruitment centers were strategically placed along the Indo-Nepal border to facilitate the movement of soldiers. The British specifically targeted the Magar, Gurung, Rai, Limbu, and Tamang communities of Mongoloid origin from central and eastern Nepal for military service. Simultaneously, the British also needed massive labor for tea plantations, road construction, and forest clearance, recruiting people of Caucasoid origin for these purposes (Subba, T., 2002).

P.C: By Unknown author – https://www.flickr.com/photos/daviddb/425742356/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2317495

This movement—military and civilian—marked the beginning of a profound cultural shift. Many communities, both Tibeto-Burman and Indo-Aryan, began to move away from their original homeland, gradually shaping a new socio-cultural identity in the Indian subcontinent.

Push and Pull: Migration in Search of Livelihood and Dignity

While British recruitment served as a key “pull factor,” a series of “push factors” from within Nepal also played a crucial role in driving migration. As documented in the late Shri K.K. Muktan’s The Comprehensive History of the Nepalis in Northeast India (Vol. I), many Nepalis fled their homeland due to extreme poverty, lack of opportunities, and an oppressive socio-political structure under the Rana and Shah autocracy.

The feudal economic system of Nepal ensured that the wealth remained concentrated with the nobility, leaving vast swathes of the population, especially farmers, as landless tenants. The rigid caste hierarchy further marginalized indigenous communities. As a result, many sought better lives across the porous border, accepting jobs as agricultural workers, cattle rearers, watchmen, peons, and laborers.

The Gorkhas in Northeast India: Settlement and Contribution

The Gorkhas began settling across British India—especially in the northeastern regions like undivided Assam, Darjeeling, and surrounding Northeast Indian areas. The British utilized them extensively in tea estates, forests, and even in local administration due to their perceived and proven discipline and loyalty.

PC: By Rebel Redcoat at English Wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by Podzemnik using CommonsHelper., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7004298

It’s been nearly 200 years since Gorkhas began to settle in Assam. Over generations, they established deep roots in the region, contributing significantly to its economic, cultural, and military life. Their presence became so integral that it’s difficult to imagine the region’s historical development without them.

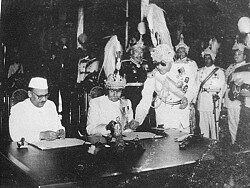

The 1950 Treaty and the Question of Identity

The 1950 India-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship further shaped the movement of people by allowing open borders between the two nations. While the treaty facilitated economic and familial exchanges, it also created confusion around nationality and citizenship—particularly for the Indian Gorkhas.

P.C: By Unknown author – Original publication: 31 July 1950Immediate source: http://www.ekantipur.com/nepal/article/?id=4877, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=56502077

The ongoing movement of Nepali-speaking people for education, work, or marriage contributed to this ambiguity (Subba, T., 2003). For Indian citizens of Nepali origin, this has led to a recurring identity crisis. The distinction between Nepalis from Nepal and Indian Gorkhas—those born and raised in India for generations—is often blurred in public perception and policy discourse.

This lack of clarity has fueled discrimination and racial prejudice. Despite being loyal Indian citizens, many Gorkhas have been subjected to racial slurs and are often misidentified as “foreigners”.

Though the Nepali language was included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution in 1992, its official status is largely confined to Sikkim and Darjeeling & Kalimpong districts of West Bengal. The Indian Gorkha community continues to advocate for broader cultural and political recognition.

Indian Gorkhas have contributed immensely to India’s defense, arts, cuisine, and public service, yet their stories are missing from mainstream Indian history textbooks. The prevailing education system continues to glorify certain kings and empires, while failing to acknowledge the grassroots contributions of diverse communities like the Indian Gorkhas (Gurung & Majumdar, 2024).

There’s a growing demand within the community for their history to be recognized in school curricula, ensuring that the legacy of Indian Gorkhas is neither forgotten nor misrepresented.

Despite their deep roots, the Gorkhas in India still find themselves in a constant struggle to assert their Indian identity. This struggle is not just about documentation—it is about dignity. Indian Gorkhas are not merely descendants of migrants; they are stakeholders in India’s history and future. Their journey—marked by loyalty, resilience, and contribution—deserves rightful acknowledgment in national narratives.

As the Gorkha community continues to grow, evolve, and advocate for its rightful place in India’s socio-political fabric, their story remains a powerful reminder of how migration, when contextualised through history and humanity, is not just movement—but transformation.

Writer’s Note

Why “300 Years of Gorkha Presence in India”?

The phrase “300 Years of Gorkha Presence in India” is not a rhetorical flourish but a carefully considered framing grounded in historical evidence. While the formal migration and recruitment of Gorkhas into the British Indian Army began after the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814–1816), historical and anthropological records trace Gorkha presence in regions now part of India—particularly in the eastern Himalayas, including Sikkim, parts of Bhutan, Darjeeling, and Assam—as early as the early 18th century (Subba, 1992; Muktan, 2020).

These early settlements occurred in a context where borders were fluid and state authority was loosely defined, especially in the Himalayan frontier zones. Over the following centuries, this presence grew—from scattered settlement and mercenary engagement to institutionalized military recruitment and broader diasporic migration across the Indian subcontinent.

As of 2025, this marks nearly three centuries of the Gorkha community’s evolving story of belonging, identity, and contribution to India—making the phrase “300 Years of Gorkha Presence in India” a historically justifiable and meaningful narrative arc.

Further Readings

- Subba, T. B. (2002). Ethnicity, State, and Development: A Case Study of the Gorkhaland Movement in Darjeeling. Har-Anand Publications.

- Subba, T. B. (2003). The Nepalis in Northeast India: A Community in Search of Identity. Indus Publishing.

- Subba, T. B. (2018). Politics of Culture: A Study of Three Kirata Communities in the Eastern Himalayas. Orient BlackSwan.

- Malley, D. (1907). Bengal District Gazetteers: Darjeeling.

- Singh, R. P. (2010). Geo-Political Position of Nepal and its Impact on Indian Security. Kalpaz Publications.

- Muktan, K. K. (n.d.). The Comprehensive History of the Nepalis in Northeast India (Vol. I).

- Gurung, L., & Majumdar, A. (2024). Scheduled Yet Obscured: A Study of Nepali Language and Identity in India. [Forthcoming]

- Muktan, K. R. (2020). Migration and Identity: The Nepalese in North-East India. Journal of Himalayan Studies and Research. Retrieved from https://www.jhsr.in/archives/articles/migration-and-identity-the-nepalese-in-north-east-india-2/

- Subba, T. B. (1992). Ethnicity, State, and Development: A Case Study of the Gorkhaland Movement in Darjeeling. Har-Anand Publications.

- The Academic (2025). “Displacement and Diaspora: Nepali Identity in Northeast India.” [Vol. 4, Issue 2]. https://theacademic.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/54.pdf

- The Academic (2025). “Migration Patterns of Nepali-speaking People in Colonial Assam.” [Vol. 3, Issue 1]. https://theacademic.in/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/102.pdf

- Scholar9 Journal (2024). “Colonial Recruitment of Gorkhas and Its Long-term Socio-Political Impact.” Retrieved from https://scholar9.com/publication/b04bcd636eecf11257aba1234ae924e1.pdf

Want to write for us? Reach out to us at indiakogorkha@gmail.com!